Calm Down, Doomers. There Is No Sign of Cultural Decline.

From Cambrian explosions to infinite Blue Oceans: the "End of Creativity" is a hallucination.

There’s a toxic idea floating through the intellectual corners of the internet. It’s not a meme or a virus, but more like a fatalistic mood: the sinking suspicion that human culture is in terminal decline.

Don’t fall for it.

Stories of doom easily go viral. Because, you know … humans. It took me two days to write this rebuttal. But critical nuance is hard to sell. I’d appreciate your help in getting the word out. Please like, share, and help me spread the message into the vast creative extremes of human culture.

The diagnosis is bleak: humanity has run out of creative ideas. We’re drowning in movie sequels, algorithmic pop songs, and story templates recycled from the previous century. Every coffee shop looks like an Apple Store, every logo is a cheerless sans-serif rectangle, and every car is an aerodynamic blob. It seems as if every hue, shade, tint, and tone is vanishing from our public space. In many designer offices, Photoshop’s color wheel sits gathering digital dust. We’re trading humanity’s glorious weirdness for a global colorless uniformity.

Multiple recent essays capture this narrative perfectly. In “The Decline of Deviance,” Adam Mastroianni argued that we’re trading weirdness for sameness, pointing out that the outliers in society (inventors, cult leaders, even serial killers) are becoming increasingly rare. In a later piece, “Our Overfitted Century“, Erik Hoel borrowed a concept from machine learning to argue that culture has become a victim of “overfitting“—so ruthlessly optimized for engagement and profit that it’s lost the ability to surprise us. Book covers, car designs, even human faces, are all trending toward the same mind-numbing optimum.

The conclusion is that we’re experiencing a cultural collapse.

Deviance is retreating.

It’s a compelling narrative. And because doom and gloom stories sell better than honest, nuanced analyses, such articles easily go viral. Confirmation bias kicks in, and everyone around the world almost wants it to be true. It certainly feels true when you’re watching the seventeenth Fast & Furious movie or having dinner in one of over fifty burger restaurants in town that all peddle some variant of a bacon burger, cheeseburger, chicken burger, and chili burger.

But as a student of complex systems, I paused at the massive contradiction staring us in the face. It’s surely the height of irony to discuss the “decline of culture” on Substack—a culture-loving platform that has single-handedly unleashed an explosion of independent writing and literally didn’t exist a decade ago.

It’s rather ironic to discuss the “decline of culture” on Substack.

To understand why the doomers are mistaken, we need to dig deeper into the mechanics of networks and complex systems.

I’m sorry. This is going to be a long post.

But it matters.

The Explosion of Novelty

In systems theory, whenever a new “solution space”—whether in biology, technology, or the economy—opens up, the result is never a polite, orderly queue. It’s a riot. It’s a mad scramble to colonize the empty space, resulting in a sudden, violent explosion of diversity.

The most famous example is, of course, the Cambrian Explosion. About 540 million years ago, the biological constraints on life suddenly shifted. In the geological blink of an eye, nature stopped iterating on simple sponges and started running batshit crazy experiments. The world saw the sudden arrival of hard skeletons, complex eyes, and body plans that would have looked spectacular in an 18th-century freak show. Nature was trying everything at once because, in an ocean devoid of competitors, there were no “wrong” answers yet.

Evolutionary biologists Eldredge and Gould called this punctuated equilibrium. They realized that history is not a slow, steady crawl of progress. Instead, systems stay boring and stable for long periods (stasis), only to be “punctuated” by swift, chaotic bursts of radical change whenever a new environment appears. Think programming languages since the 1960s. Or applications in Apple and Google app stores. Or remote and hybrid working technologies since Covid-19.

We see the same pattern in human technology everywhere. When the printing press arrived in the 1500s, we didn’t just get Bibles; we got a flood of pamphlets, heretical manifestos, and primitive newspapers. When the World Wide Web broke open in the 1990s, we didn’t immediately get the clean, standardized aesthetic of corporate websites. We got the blinking chaos of GeoCities, dancing baby GIFs, and websites printed in yellow text on bright blue backgrounds. It was ugly, weird, and gloriously diverse.

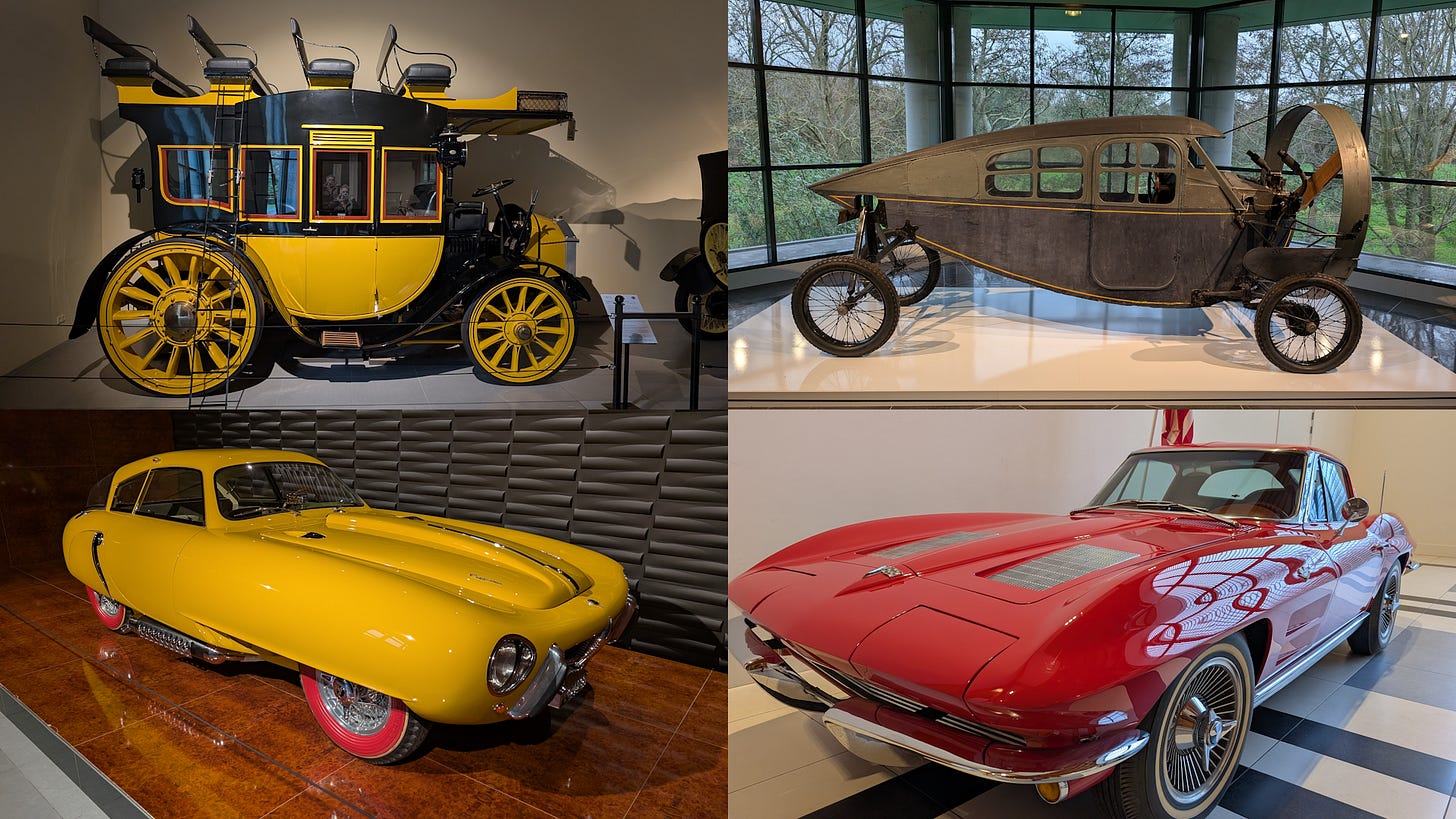

Or look at the automobile. In the first half of the 20th century, before the rules for the car industry were written, there was a Cambrian explosion of automotive madness: cars with three wheels, cars steered by tillers, and cars that looked like horse carriages with invisible horses. There was even a double-decker car that would likely struggle to remain viable in 2025.

Complexity researchers have a beautiful term for this: the adjacent possible. Imagine you’re in a room with four doors. When you open one, you don’t just enter a new room; you might reveal three new doors that were previously inaccessible. Each innovation expands the boundaries of what’s possible next. In the early stages of a new environment, the “adjacent possible” is wide open. The constraints are low, the potential is high, and the “cost of being weird” is effectively zero.

In the business world, this is the Blue Ocean Strategy. It’s when someone creates an entirely new market space where competition is irrelevant because there’s only one entity swimming there. It’s Ford’s Model T in 1910 or America Online in 1999. They aren’t fighting for scraps in a crowded shark tank; they’re exploring a vast, empty ocean.

But here’s the catch: a valuable empty ocean doesn’t stay empty forever.

As the solution space fills up with new entrants (organisms, books, websites, car companies), the physics of the system change. The era of “anything goes” ends, and the pressure to survive starts mounting.

The Crush of Conformity

As the solution space fills up, the rules of the game change. In ecology, this shift is described by r/K Selection Theory:

r-selection (Quantity): When the environment is empty and chaotic, the best strategy is to be like a weed or a bacterium: reproduce fast, try a thousand different things, “move fast and break things,” and hope something survives. This is the era of the garage startup and the experimental artist.

K-selection (Quality): When the environment gets crowded, the strategy flips. Now you must be like the elephant: reproduce slowly, but invest massive resources into making sure your offspring survives the competition. This is the era of the conglomerate and the blockbuster franchise.

When an environment matures, it leaves the frivolous “r-phase” and enters the ruthless “K-phase.” In systems theory, we say the fitness function has tightened. This “function” is simply the mathematical sum of everything that’s needed to survive the things trying to kill a system: physics, regulations, production costs, and the fickle attention of the audience. When a market is new, the function is loose (you can be weird and still succeed). But as the market matures, the function becomes rigid (you must conform to every expectation or you’re out of the game).

Example: early aviation was a chaotic playground of triplanes, pusher-props, and experimental engine placements—three engines, four engines, under the wings, on the wings, under the tail, on the tail—because designers and engineers were mostly still guessing. Today, all that guessing is over. Physics and fuel efficiency act as ruthless filters, forcing all commercial aircraft to converge on a single, soul-crushingly optimal solution: the “tube-and-wing” design with one engine under each wing. It’s the only design you’ll see at Schiphol and Heathrow airports.

What I’ve described here is the phenomenon known as convergent evolution. Nature and designers eventually discover the “optimal” shape. This is also why sharks (fish) and dolphins (mammals) look nearly identical despite being completely unrelated. Their fitness function doesn’t care about their biological ancestry; it only cares about hydrodynamics.

Convergent evolution also happens in our culture.

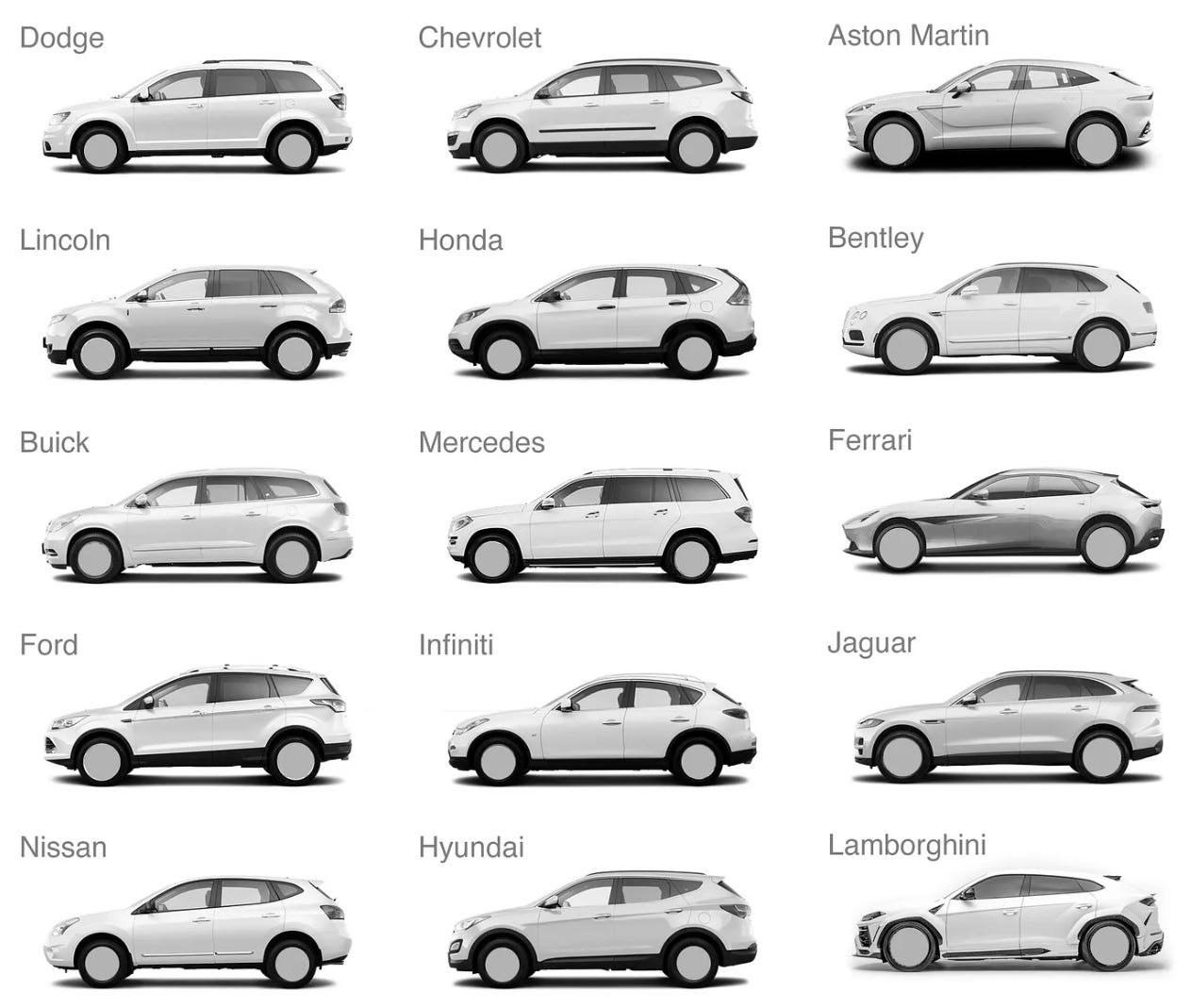

Modern cars share a uniform silhouette not because designers have lost their souls or lack creative flair, but because the fitness function of aerodynamics, safety regulations, and customer preferences dictates the geometry. If a manufacturer deviates too far from the standard shape, they end up with a car that’s either unsafe, illegal, or undesirable.

Even the internet has been tamed by the same force of convergence. Back in the 90s, the web was a wild west of creative design. Today, every website looks identical. Why? Because they’re optimizing for the fitness function of the user’s brain, also known as Jakob’s Law: Users spend most of their time on other sites.

This means that if your website works differently than everyone else’s, the user gets frustrated and leaves. In the late 90s, you could get away with that. Hell, back in those days you’d get bonus points for weirdness and originality! But in 2025, you must conform to a long list of mental models your visitors already have (not to mention the technical requirements of bots and web scrapers). Nobody wants to relearn where to find the product pricing plans, terms of service, or “Contact Us” button, just to satisfy the ego of some web designer who considers herself an artist. Those days are long gone.

This is the reality of the red ocean. It’s a bloodied, contested environment where the only way to survive is to conform to the norm and look very much like the fittest specimen in the ecosystem—only slightly cheaper, prettier, or faster.

The doomers are right, to some extent.

“Creative fields have become dominated and defined by convention and cliché. Distinctiveness has died.”

- Alex Murdell, “The Age of Average.”

Do you like this post? Please consider supporting me by becoming a paid subscriber. It’s just one coffee per month. That will keep me going while you can keep reading! PLUS, you get my latest book Human Robot Agent FOR FREE! Subscribe now.

The Same, But Different

So, if the fitness function is forcing everything to look the same, does that mean creativity is dead? Is culture declining?

Not quite, for several reasons. First, it just means creativity has moved to the edges.

I remember a time when supermarkets sold only a few types of hagelslag (chocolate sprinkles) and pindakaas (peanut butter) in my country. Nowadays, when I look in the bread toppings aisle, I see plain pindakaas, crunchy pindakaas, creamy pindakaas, almond pindakaas, hazelnut pindakaas, vegan pindakaas, low-salt pindakaas, 100% pure pindakaas, pindakaas light, pindakaas without palm oil, pindakaas with honey, pindakaas with chili pepper, pindakaas with lemon grass, and much more. There’s even pindakaas with garlic and onion. Talk about weird! And don’t get me started on all the varieties of sprinkles we can get.

These products are “all the same” in the sense that they’re offered by just a handful of brands and must all satisfy the same physical constraints of transport logistics, supermarket shelves, public health regulations, and the intricacies of consumer pricing. But there’s endless diversity in the details. My local store has more different kinds of peanut butter than I’d care to try in a year. Culturally speaking, the Dutch have stopped consuming the same pindakaas and hagelslag. That’s not cultural convergence; it’s cultural divergence.

In a saturated red ocean system, you’re no longer allowed to reinvent the frame, which has been optimized by physics, governance, and the market. Instead, you have infinite freedom to reinvent the patterns: the exchangeable elements within the mandatory constraints.

To understand these mechanics, let’s look at two laws that govern the concept of being weird.

First, there’s Hotelling’s Law: Imagine two ice cream carts on a mile-long beach. To maximize sales, they won’t space themselves out politely at opposite ends. No, they will eventually shuffle close to each other in the dead center of the beach, fighting for the massive middle ground. That’s why the diamond shops in Antwerp are all clustered on the same streets.

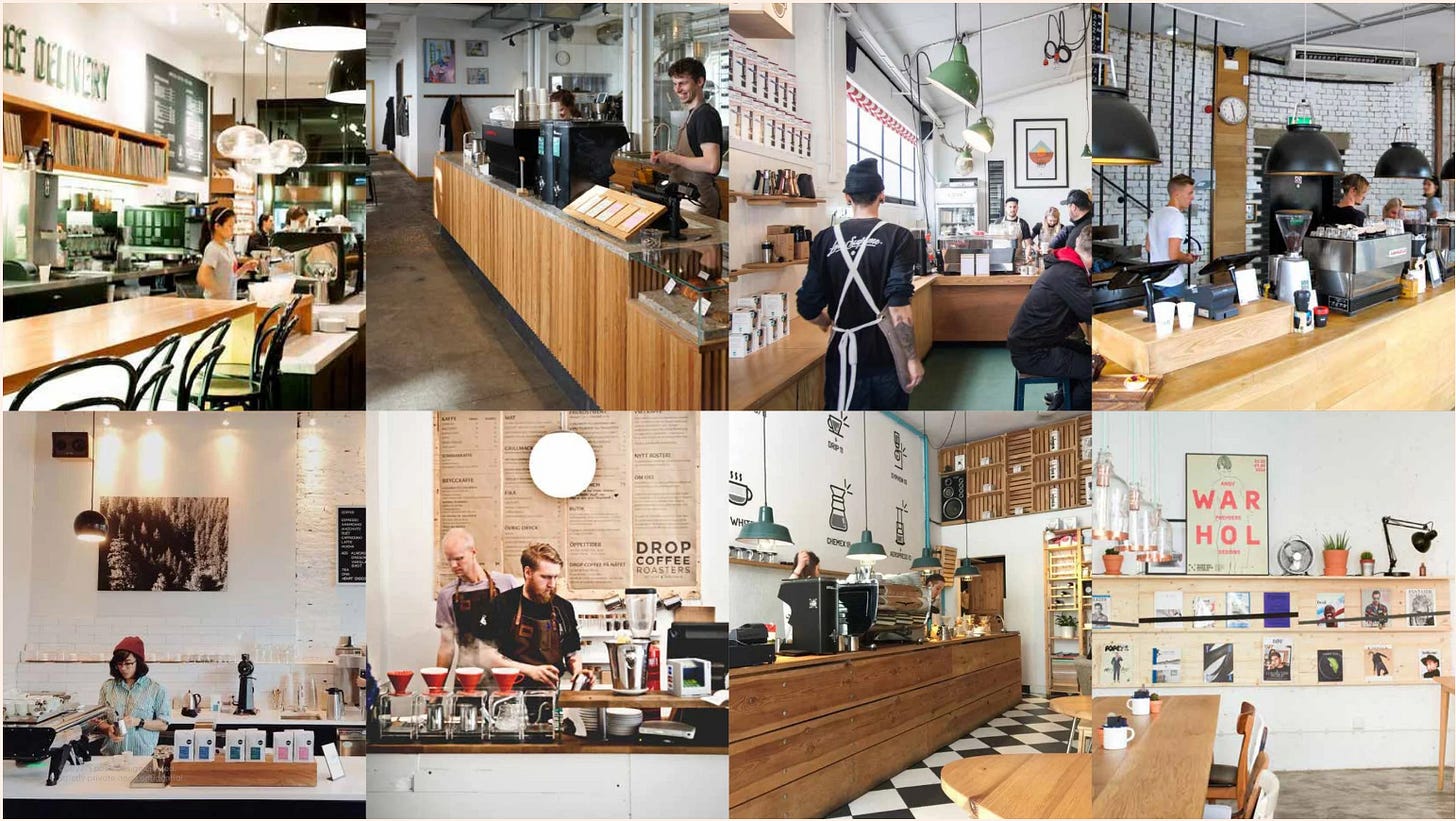

This is the principle of minimum differentiation. It explains why every coffee shop opens in the same part of town as the other coffee shops, and why they all serve the same espressos, americanos, cappuccinos, and flat whites. Being “too different” (moving to the empty far end of town) is risky. You might lose the crowd.

Second, there’s the MAYA Principle, coined by the legendary industrial designer Raymond Loewy. It stands for “Most Advanced Yet Acceptable.” Loewy realized humans are contradictory: we crave novelty, but we’re terrified of the unfamiliar. If you design a car that looks like a spaceship, people won’t buy it. They need a “bridge” to the future. To sell something new, you must make it familiar. To sell something familiar, you must make it surprising.

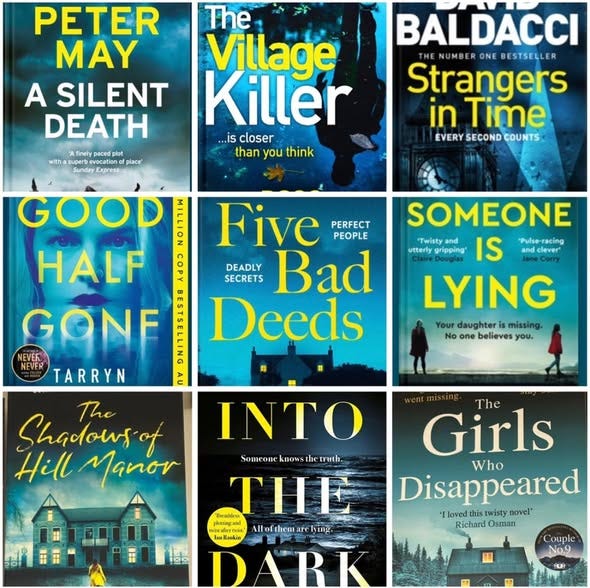

These two forces—Hotelling and MAYA—create a “mandatory baseline.” They’re the reason every thriller novel has the same bold typography, high-contrast font and shadowy figure on the cover. If you don’t follow the trope, the reader’s brain doesn’t file you under “thriller,” and you don’t get bought.

So, if Hotelling and MAYA force you to be the same, how do you win?

Well, you could deploy the Kano Model. This framework by Noriaki Kano categorizes features into “must-haves” (the coffee must be hot) and “delighters” (the latte art is a swan). In a mature market, the “must-haves” are identical for everyone. When Tesla entered the EV market, it couldn’t compete on having “better” wheels, doors, or seats; those problems were already solved. But they could compete on “delighters,” like extended battery life, central touch screen, fancy door handles, funny Easter eggs, and over-the-air software updates.

This also brings us to Seth Godin’s concept of the Purple Cow. In a field of identical black-and-white Holstein Friesian dairy cows (the “safe” choice as dictated by Hotelling’s Law), the only way to survive is to be a purple cow—something so distinct, in a non-essential way, that it forces people to stare. It’s still a cow, like all the others, but it’s one that stands out.

This is the state of modern culture: tremendous diversity but limited within constraints. This isn’t “overfitted” to death; it’s highly optimized at the core and wildly experimental at the edges.

Coffee Shops: They all look the same (reclaimed wood, Edison bulbs) because that’s the MAYA “language” of comfort. But they differentiate violently on the “delighters”—the single-origin beans, the nitrogen-infused cold brew, the vegan cronut or crompouce.

Book Covers: They follow rigid genre templates so you know instantly what you’re buying (Hotelling). But within that template, the artists fight tooth and nail to create a title or an image that still draws attention on a smartphone screen and makes you stop your scroll (Purple Cow).

For another example, consider TV series. In the 80s, shows like The Hulk, A-Team, Knight Rider, Airwolf, and MacGyver all followed the same strict formats, optimized for ad-dominated broadcast TV aimed at large audiences. They were all the same length, with breaks at the same times, and stories that wrapped up in one hour. And everything had to be family-friendly!

Nowadays, there’s extreme diversity in characters and plots in TV shows because streamers are constantly pushing the boundaries of what’s socially acceptable, with endless variety in representation, identities, relationships, sex, and violence catering to niche markets. The time constraints per episode are gone, replaced by new constraints on binge-ability. Again, that’s not cultural convergence; it’s cultural divergence.

No, humans haven’t stopped innovating. In crowded markets, they’ve just moved the innovation from the category level to the feature level.

The Decline of the Average

If evolutionary pressure explains why things look similar, network theory explains who will win. And in a globalized network, the winner takes almost everything.

To understand the architecture of our culture, we must look at two concepts that act as the gravity of the internet.

The first is preferential attachment, popularized by network scientist Albert-László Barabási. In a growing network, new nodes don’t connect randomly. They attach to nodes that already have the most connections.

“Fewer and fewer of the artists and franchises own more and more of the market.”

- Adam Mastroianni, “The Decline of Deviance“

Why do we do this? Because of René Girard’s Mimetic Theory. Girard argued that human desire is not autonomous; it’s collective. We don’t just want things; we want what other people want. We watch the trending shows and films because they’re trending. We read the bestselling books because they’re bestsellers. And each Top 10 list on Netflix, Spotify, and Amazon only speeds up this effect.

These two forces—preferential attachment and mimetic desire—create the Matthew Effect: the mathematical version of “the rich get richer.”

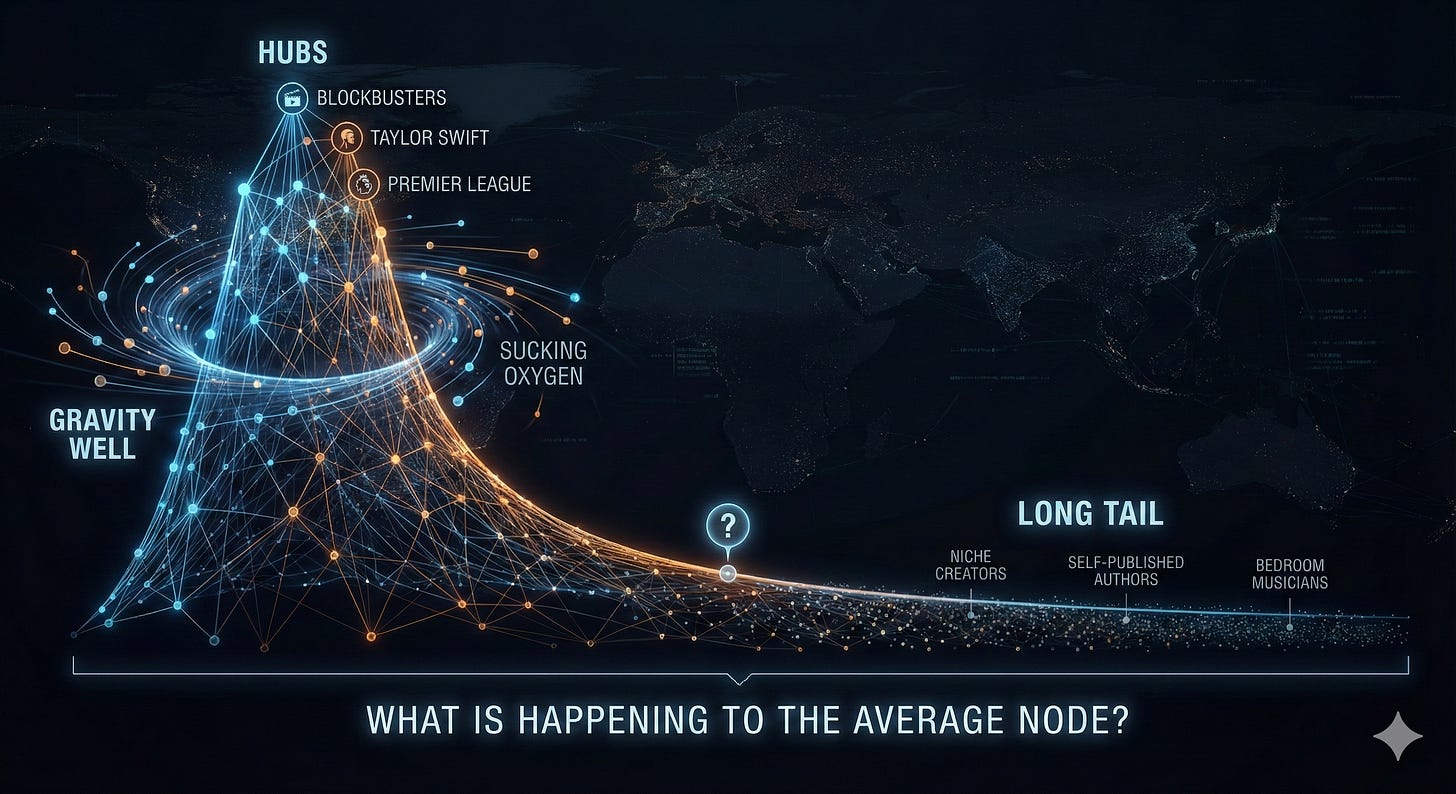

The result is a “deepening curve.” On the far left, you have the hubs: the blockbuster movies, Taylor Swift, the Premier League. These winners are so massive they create a gravity well, sucking the oxygen out of the room. On the far right, you have the Long Tail: millions of niche creators, self-published authors, and bedroom musicians whose cost of creation has dropped to zero, but who struggle to find an audience of more than a few people.

The pessimists look at this curve and ask the critical question: “What’s happening to the average node?” They see a world where the recommendation algorithms herd us all toward the peak while the long tail stretches out into an infinity of weirdness and obscurity. They argue that the “average middle”—the place where moderate success used to exist—is disappearing. And they’re right!

This is the Barbell Effect.

The weights are massive on the left (a few nodes with high volume: the superstars) and also massive on the right (countless nodes with low volume: the niche crowd). But the ones that used to earn a living in the middle—the mid-budget movie, the national pop star, the regional newspaper—are being pulled apart between the superstars and the niches.

Consider the tragic fate of the banana.

Across the tropics, there are roughly 1,000 distinct varieties of bananas and plantains. They come in red, purple, and green; some taste like vanilla, others like apples. This is the long tail.

But if you walk into a random supermarket in New York, London, Tokyo, or Rotterdam, you’ll find only one kind: the Cavendish. The Cavendish is the hub. It’s the Taylor Swift of fruit: genetically identical, optimized for shipping (the fitness function), and universally recognizable. It dominates international trade so completely that for most humans, “banana” equals “Cavendish.”

The “average banana”—the regional variety that’s pretty good but not global-standard—has been practically erased from the market.

What makes this feel so intense is that globalization has poured gasoline on the fire. In the past, local cultures had “local hubs.” You had a famous local singer and a popular local sport. Today, the network is global. The “local hub” can’t compete with the “global hub.” It’s why in the Netherlands, Facebook replaced Hyves, eBay bought Marktplaats, and Amazon is now threatening BOL.com.

And this consolidation happens faster than ever. A trend on TikTok doesn’t take years to spread; it takes days or hours and doesn’t stay confined within national borders. This means the cycle of the Cambrian explosion (new trends) and Matthew Effect (everyone copying the trends) is happening at warp speed.

For example, the Dubai chocolate bar, combining pistachio cream, kadayif and chocolate, became a global TikTok‑driven phenomenon in 2024. The flavor profile quickly inspired local bakers to experiment with seasonal products. In my country, bakeries and street vendors started selling “Dubai-bollen,” as a variation on the typical Dutch delicacy of oliebollen (fried dough, often with raisins). The time it took from the emergence of the hype to “Dubai oliebollen,” sold across the country, was only several months. But one thing is certain: Dutch bakeries sell more varieties of oliebollen than before. Their assortment has expanded, not contracted. It signals the divergence, not convergence, of Dutch eating habits.

Summarized, we’re not just seeing a collapse of the middle; we’re witnessing the catalyzation of variety.

The Shifting Landscape

There’s another major flaw in the logic of the doomers: they assume the environment stands still. They act as if the rules of the game are static.

But in complexity science, we know that the environment is dynamic. We’re not just climbing a mountain; the mountain is changing shape underneath our feet. This is known as the fitness landscape.

Organisms (and products and ideas) engage in an adaptive walk across this changing landscape. They climb toward the nearest peak of “fitness.” But occasionally, an earthquake happens. The peak collapses into a valley, and a new peak rises somewhere else. New constraints replace the constraints of the past, forcing all products to change course and walk in another direction. It’s why songs have adapted for streaming. It’s why car designs are adapting for a rideshare economy.

Consider why logos, book covers, and film posters have become increasingly simplified. The critics call it “blanding” or “converging.” They say designers have lost their mojo. But look at the landscape of business. A new massive constraint has been added to the fitness function: visibility on the smartphone screen.

In the 20th century, a movie poster had to catch your eye from across a street. Today, it has to be legible as a tiny thumbnail on Netflix. If your logo is a complex, heraldic crest, it looks like a smudge on an iPhone. So, the system adapts. We stripped away the details not because we hate beauty, but because the environment demanded recognizability at sixteen millimeters tall. We didn’t “lose” our creativity; we just optimized it for a world made of thumbnails.

However, the landscape doesn’t just add constraints; it also removes them. And when a heavy constraint is lifted, diversity explodes!

Look at gender and identity, for example. For the Victorian era (and much of the 20th century), the social fitness function imposed a brutal constraint on gender, identity, and sexual attraction. You had to fit the binary mold, or else you were socially exiled. You’d be literally called a deviant.

But since the 1970s, that constraint has steadily lifted, with an acceleration happening in the 2000s. The result is an immediate, powerful adaptive walk away from the binary norm. Society is moving from a rigid “two-option” system to a diverse spectrum involving dozens of distinct orientations and identities. (It takes just one peek in my favorite coffee bar in Rotterdam to find that the traditional heterosexual cis-male has almost become an endangered species!)

This is the paradox of our time: while our corporate logos are converging into uniformity (tightening constraints), our personal identities are diverging into a kaleidoscope of variety (loosening constraints). The landscape is shifting in all directions, with convergence in one area offset by divergence in another.

Do you like this post? Please consider supporting me by becoming a paid subscriber. It’s just one coffee per month. That will keep me going while you can keep reading! PLUS, you get my latest book Human Robot Agent FOR FREE! Subscribe now.

Infinite Blue Oceans

Last but not least, if every category eventually becomes a blood-soaked red ocean—a barbell world of massive winners and countless deviants—is culture doomed? Are we destined to watch the same five businesses compete for our attention across all categories?

Not if you look at the birth rate of the categories themselves.

Thirty years ago, “entertainment” meant books, TV, and movies. That was it. Today, that label has stretched to cover entirely new species of human activity: podcasting, live streaming, generative fiction, cloud gaming, game streaming, online gambling, crypto speculation, immersive theatre, escape rooms, and virtual/augmented reality have spawned new empires that have completely bypassed the traditional gatekeepers.

Or consider the world of sports. Thirty years ago, the “solution space” for physical activity in my town was limited to football, basketball, and perhaps tennis, for those who could afford it. Today, the landscape has fractured into a thousand new tribes: Padel, DEKA, Hyrox, Teqball, pickleball, Spartan‑style obstacle races, parkour chase tag, drone racing, competitive CrossFit, e‑sports. Reading off the entire list is already exhausting in itself!

We aren’t just fighting over the same territory anymore. We’re creating hundreds of wonderfully strange, new, unrecognizable competitive spaces.

To be fair, the cynics have a strong counterargument here. They’ll argue that this is “fake” diversity. This is what some call the “Silent Collapse.” It suggests that while we have more categories, they’re all being subtly homogenized by the platforms that host them.

If a new sport like “drone racing” is filtered through the Instagram algorithm, does it really count as true innovation? Or has it just been formatted into a vertical, 15-second loop of “content” to sit alongside the funny cat videos? All entertainment options have one thing in common: they compete for the same limited human attention span. If every new subculture has to advertise via TikTok and monetize via Patreon, are we really seeing new forms of entertainment, or just infinite flavors of the same digital slop?

It’s a valid concern. The medium is the message, and the medium is currently a smartphone or tablet screen.

But here’s where we must deploy our final mathematical weapon, the one that overrides the pessimism of the Silent Collapse.

Recall that the adjacent possible is the set of all things that can happen next. Crucially, this set doesn’t grow linearly; it grows exponentially!

When you invent the wheel, you unlock the cart. When you invent the cart and the steam engine, you unlock the train. When you invent the train, the telegraph, and the stock market, you unlock the industrial supply chain. Every new invention is a LEGO brick. And the more bricks you have, the more combinations you can build.

We’re not just adding “new apps.” We’re throwing the most potent LEGO bricks in history into an ever-growing pile: AI, spatial computing, 3D printing, nanotechnology, bio-hacking … the list goes on and on. That’s one hell of a pile to turn into new innovations!

We’re entering a phase where the “cost of trying” in the physical world is dropping to zero, just as it did for the digital world. We’re about to see the long tail applied to biology, to matter, to energy.

To assume that this massive injection of complexity will result in a boring, uniform culture is to bet against the fundamental laws of chaos and complexity. The network algorithms might drive us to converge on the same, but the combinatorics of the universe are pulling us toward what’s deviant.

Conclusion: The Unpredictable Average

Why are people so eager to believe in the demise of human culture?

The answer lies less in the data and more in our DNA. Humans have a well-documented negativity bias. We’re evolutionarily wired to notice the tiger in the bushes (the threat) rather than the beautiful sunset (the opportunity). We look at the consolidation in Hollywood and scream “Collapse!” while ignoring the millions of kids inventing entirely new art forms on platforms we haven’t even heard of yet.

This gloom is compounded by declinism (or rosy retrospection)—the psychological trap where we view the past as a “Golden Age” of creativity and the future as a wasteland. When critics sigh that “people are less weird than they used to be,” they’re suffering from survivorship bias. They cherry-pick their examples of convergence while remaining blissfully unaware of the vast diversification that has never even reached their span of attention.

The fundamental mistake these critics make is assuming that culture is a single, static container. They act as if we’re fighting over a fixed number of pies—movies, books, pop songs. And yes, if you only look inside those long-established boxes, things are indeed getting boring. The Matthew Effect is brutal there.

But by forcing the entire definition of “culture” into these shrinking boxes, the critics are guilty of what Nassim Taleb calls the Bed of Procrustes fallacy. Like the mythical Greek innkeeper who stretched or chopped off his guests’ limbs to fit the bed, doomers chop off the messy, expanding reality of culture to fit their crisp narrative of decline.

One last example, because I wrote this in English, which is not my native tongue: consider the fate of language itself. The relentless pressure for global connectivity is forcing a massive consolidation toward English—or rather, “Globish,” a simplified, utilitarian tool for international trade and communication. Lamenting the death of local dialects and small languages is valid; the structure of spoken language is undoubtedly morphing into a single linguistic hub.

But look at the surface of digital communication. Freed from the constraints of formal grammar textbooks, we’re witnessing a Cambrian explosion of non-verbal expression. We communicate complex emotional states with carefully chosen emojis, exchange inside jokes with memes, and paint pictures with ASCII art. The world may converge on a single tongue, but our thumbs are inventing alternative forms of communicating every day.

We aren’t seeing a fixed set of cultural curves deepening; we’re seeing a recursive fracturing of the network. Every time a new category is born—whether it’s “professional knitting streamers” or “generative AI artists”—it starts a new curve. It begins with yet another Cambrian Explosion before the Matthew Effect eventually sets in. And on and on it goes; again and again, this repeats.

The ultimate rebuttal to cultural pessimism is a concept from physicist Stephen Wolfram called computational irreducibility. It states that for a truly complex system, there’s no shortcut to predicting the outcome. You can’t derive a simple formula that tells you where culture will be in 50 years based on the trend lines of today. You can’t extrapolate the end of art from the decline of the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

To know the answer, you must run the program. You have to live through it.

So, is the “average” dead? Is culture in decline?

No.

Some areas are converging; other areas are diverging. But the one thing culture won’t be is “overfitted.” The available theory simply doesn’t support that conclusion.

The “Collapse of Culture” is a hallucination.

Jurgen

P.S. Stories of doom easily go viral. Because, you know … humans. It took me two days to write this rebuttal. But critical nuance is hard to sell. I’d appreciate your help in getting the word out. Please like, share, and help me spread the message into the vast creative extremes of human culture. Humanity deserves it.

The Business Model Canvas Graveyard

Artificial intelligence is delivering the killing blow to an already oversaturated market of knockoffs and copycats.

It's Not Always Cold in the True North

AI cannot interpret corporate bullshit or fill gaps with common sense like humans do. As AI systems make more decisions on behalf of companies, vague mission statements and meaningless values become operational liabilities that expose the gap between what organizations claim to stand for and what they actually do.

You Cannot Please Everyone

The only good reason for writing posts complaining about other people’s usage of AI is when your audience consists of snobbish, patronizing fools.

This maps cleanly to fitness functions tightening as systems mature. Convergence at the category level is exactly what you’d expect. Blue oceans close, red oceans form, and surface forms optimize for survival under shared pressures. The key variable is where that constraint lands.

Deep constraints usually sharpen meaning and experimentation, while constraints optimized for external legibility, scale, and platform distribution compress everything at the interface. What looks like cultural decline is often just a loss of visible fidelity caused by that surface level optimization, not an exhaustion of creative capacity.

Great piece. Reminds me of the arrow metaphor, a great pulling back effort before being shot into the distance. I am fully convinced of , there can never truly be a lack of creativity!