The Business Model Canvas Graveyard

AI Is Making Visual Templates Obsolete

Artificial intelligence is delivering the killing blow to an already oversaturated market of knockoffs and copycats.

Like many sociotechnical innovations, it started with a good idea.

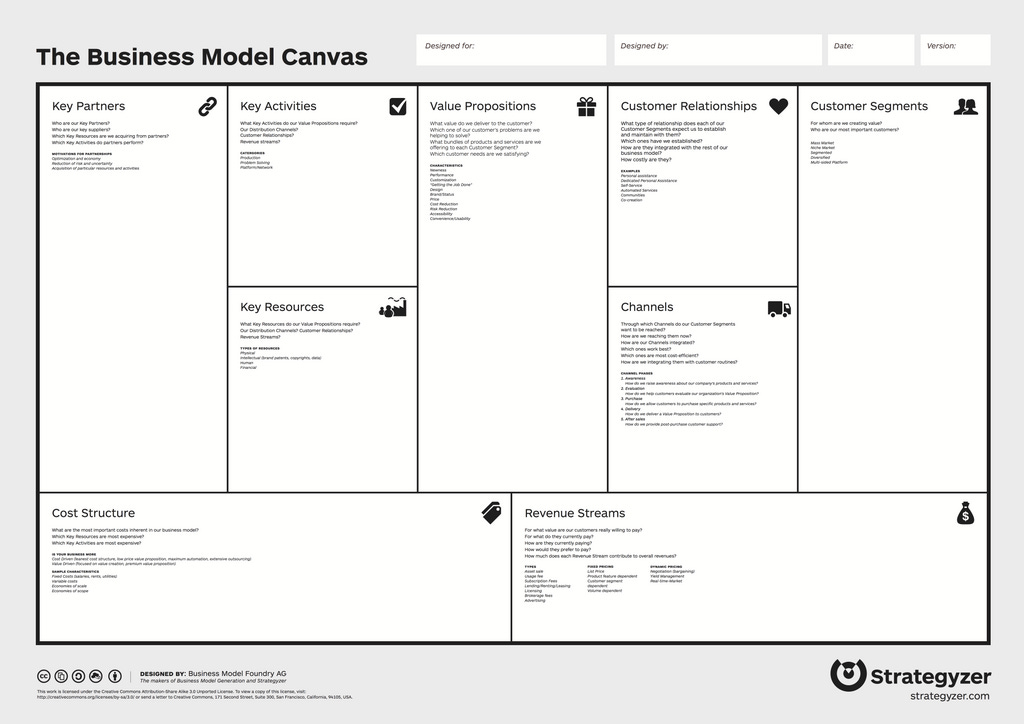

Alexander Osterwalder, a Swiss business theorist and entrepreneur, created the Business Model Canvas as part of his PhD work on business model ontology in 2005. He refined it with his supervisor, Yves Pigneur, and they turned it into a phenomenon through their 2010 bestselling book Business Model Generation. Practitioners contributed feedback during development, which helped polish the final template into the tool that has plastered conference room walls worldwide ever since.

Then the world lost its mind.

We got the Lean Canvas, Value Proposition Canvas, Mission Model Canvas, Opportunity Canvas, Product Canvas, Product Strategy Canvas, Platform Design Canvas, Platform Value Canvas, Team Canvas, Team Agreement Canvas, Culture Design Canvas, Ethics Canvas, Operating Model Canvas, Change Canvas, Change Management Canvas, Lean UX Canvas, Game Design Canvas, Service Logic Canvas, Social Business Model Canvas, Flourishing Business Canvas, Culture Map Canvas, Empathy Map Canvas, Gamification Model Canvas, Open Innovation Canvas, Business Model You Canvas, Stakeholder Analysis Canvas, Pitch Canvas, and approximately nine hundred others.

Every consultant who could draw rectangles on a PowerPoint slide, and who was able to download a Creative Commons logo, decided they should have their own canvas.

There’s even an AI Canvas.

And a Canvas Canvas.

Surprising? Not even slightly.

Do you like this post? Please consider supporting me by becoming a paid subscriber. It’s just one coffee per month. That will keep me going while you can keep reading! PLUS, you get my latest book Human Robot Agent FOR FREE! Subscribe now.

The Star and the Copycats

The Rubik’s Cube tells you everything you need to know about what happens after a breakthrough. Ernő Rubik invented the well-known puzzle in the 1970s; it hit global markets in 1980, and suddenly everyone wanted one. Hundreds of millions of units sold. The thing embedded itself in popular culture, education, competitive speedcubing—everywhere. I was absolutely in love with it when I was ten years old.

What followed was predictable. Manufacturers cranked out near-identical twisty puzzles with similar colors and mechanics. Cheaper, shoddier, and forgettable. These knockoffs got labeled as generic toys instead of iconic objects. No brand equity. No staying power. Just short-term novelty sales and unlicensed garbage collecting dust in discount bins.

The original puzzle created by Rubik dominated so completely that people still say “Rubik’s Cube” when they mean just any 3×3 twisty puzzle. That’s not just brand success—that’s entire category ownership. And the imitators are barely footnotes in history.

The pattern doesn’t stop with toys.

The Agile Manifesto became the blueprint for every niche and profession that wanted its own values document. The original was short, memorable, explicitly framed as a values-based revolt against heavyweight, document-driven processes in software. The simple format felt powerful, replicable, and unmistakably impactful.

Once Agile spread beyond software, everyone started publishing manifestos. The Software Craftsmanship Manifesto. The Project Management Declaration of Interdependence. Each copycat remixed or extended the original for a specific community. Eventually, the term “manifesto” became a rhetorical device in product management, UX, DevOps, HR, marketing—anywhere someone wanted to sound Important and Aligned. The result was an endless stream of Agile-inspired knockoffs that borrowed the structure and tone but never achieved the same unifying influence.

More examples, because why not:

Uber’s rapid scaling spawned local clones everywhere. Bolt in Europe, Ola in India, Didi in China—all following the same app-plus-driver model. A few regional competitors grew strong. But the smaller ride-hailing startups never achieved comparable scale or funding and vanished in waves of consolidation.

Similarly, Harry Potter’s success led to a flood of school-for-magic and chosen-child fantasy series. Many borrowed similar tropes and story structures. Some sold well enough. But none of these imitators matched Harry Potter’s multi-generation fan culture, transmedia franchise scale, or sustained sales profile.

This pattern repeats because it’s structural, not accidental.

This is how networks work.

A single striking success becomes the hub that everyone else orbits. The original, whether it’s Rubik’s Cube, the Agile Manifesto, or a popular product or platform, captures most of the network effects, people’s mindshare, and cultural vocabulary. The later entrants get evaluated in reference to the original instead of on their own terms.

Copycats appear in bursts, drawn by visible success. They imitate surface features: look, wording, mechanics. They rarely replicate the original’s distribution networks, communities, or narrative. So they flare briefly, then fade or consolidate. Meanwhile, the original creates a gravity well that shapes the entire category. And even when people adopt alternative products, the mass market keeps using the star’s name as the generic label. That reinforces dominance and keeps clones in the shadow.

Last week, someone asked me, “Will you take an Uber home?”

“Yes,” I replied. But I actually opened the Bolt app.

Do you like this post? Please consider supporting me by becoming a paid subscriber. It’s just one coffee per month. That will keep me going while you can keep reading! PLUS, you get my latest book Human Robot Agent FOR FREE! Subscribe now.

The End of the Flood of Canvases

Right. Back to my actual point. Because I’m sure you’ve got work to do.

The Business Model Canvas and its nine hundred clones are on their way out. Not because they were bad ideas, but because the underlying benefits got disrupted.

What did a canvas actually do for people?

First, visual templates facilitate discussion. I’ve run enough workshops to know that humans find it easier to talk about abstract topics—value propositions, stakeholder problems, platform strategies—when they can point at a diagram and move pieces of paper around. The tactile element matters. But the canvases themselves don’t facilitate discussions. For that, you need a coach, consultant, or facilitator.

But how much of that do we still need when ChatGPT is sitting there, waiting to poke its digital nose into everything we do?

These days, people turn to AI for 24/7 guidance on personal and business matters. Self-help tools are the most popular category in AI products. And an avalanche of AI agents is invading the workplace. Why wait for a human facilitator when Claude or Gemini can guide the conversation cheaper, faster, and without wallpapering the corporate walls with sticky notes?

Second, visual models communicate outcomes to stakeholders. “Look at our value proposition canvas. We made tremendous progress in identifying the assumptions behind our solution and our customer’s problem!” Great. AI can generate that visual in seconds now.

For example, many workers have discovered that Google’s NotebookLM and Nano Banana Pro are extremely good at generating diagrams and infographics on the fly from simple prompts. Other models and products will follow. You can feed meeting notes into a machine and get a compelling visual that captures your team’s entire discussion … in Studio Ghibli colors. With a Star Wars theme. Or every participant drawn as a Muppet. There’s no Creative Commons-compliant, downloadable PDF that can do that for you.

Third, the human brain craves progress. We like small steps toward objectives, ticking items off lists, and feeling completion when we’re done. The thousand canvases available to us let us feel progress on whatever abstract topic confuses us. “Six boxes done. Four more to go, and then we have a complete team agreement. Woo-hoo!”

But how relevant is that when you can throw any task list into an AI-enabled, gamified tool that rewards you for accomplishments? Sure, putting colorful paper on a large canvas feels gratifying. Once. Meanwhile, AI-powered tools give you stars, stickers, and encouragement every day. A canvas template just tells me, “download complete.” My buddy Zed tells me, “Congratulations, you filled in ten boxes … shame none of them required a functioning brain.” Because he’s an asshole. But I prefer Zed to a PDF.

The Business Model Canvas was innovative. Twenty years ago.

Then, a thousand knockoffs and copycats arrived and diluted the magic.

Now, the killing blow has arrived. The AIs walked in with a shredder.

I have no need for canvases anymore. I simply talk with my team of AI buddies; they ask difficult questions, deliver critical reviews, and generate fancy diagrams to visualize my thoughts. We mark things as done, and we move on.

No canvases get hurt in the process.

Not even used.

Jurgen

A Map for Agentic Transformation

Real agentic transformation requires navigating complex organizational tensions and contradictions that no simple ladder can capture.

It's Not Always Cold in the True North

AI cannot interpret corporate bullshit or fill gaps with common sense like humans do. As AI systems make more decisions on behalf of companies, vague mission statements and meaningless values become operational liabilities that expose the gap between what organizations claim to stand for and what they actually do.

Spot-on analysis! The flood of visual templates never solved the real problem, structured thinking and actionable insights. AI now steps in to generate diagrams, challenge assumptions, and synthesize discussions in ways static canvases never could.

I talk about the latest AI trends and insights. If you’re interested in practical AI strategies for creators and teams navigating the shift from traditional templates to AI-driven workflows, check out my Substack. I’m sure you’ll find it very relevant and relatable.

Really enjoyed this article. I was in business school when this fad was in full force and I never quite understood the draw (pun intended). Your point about AI being the real disruptive force has a ring of truth to it: people don’t need more boxes to fill in; they need guidance, critique, and the freedom to iterate. Feels like we’re finally moving from templates to conversations.