The Tragedy of the Agents

Skills are the new patterns and practices. And that might be a problem.

Clayton Christensen’s framework lives inside Claude now. I don’t even need to understand it.

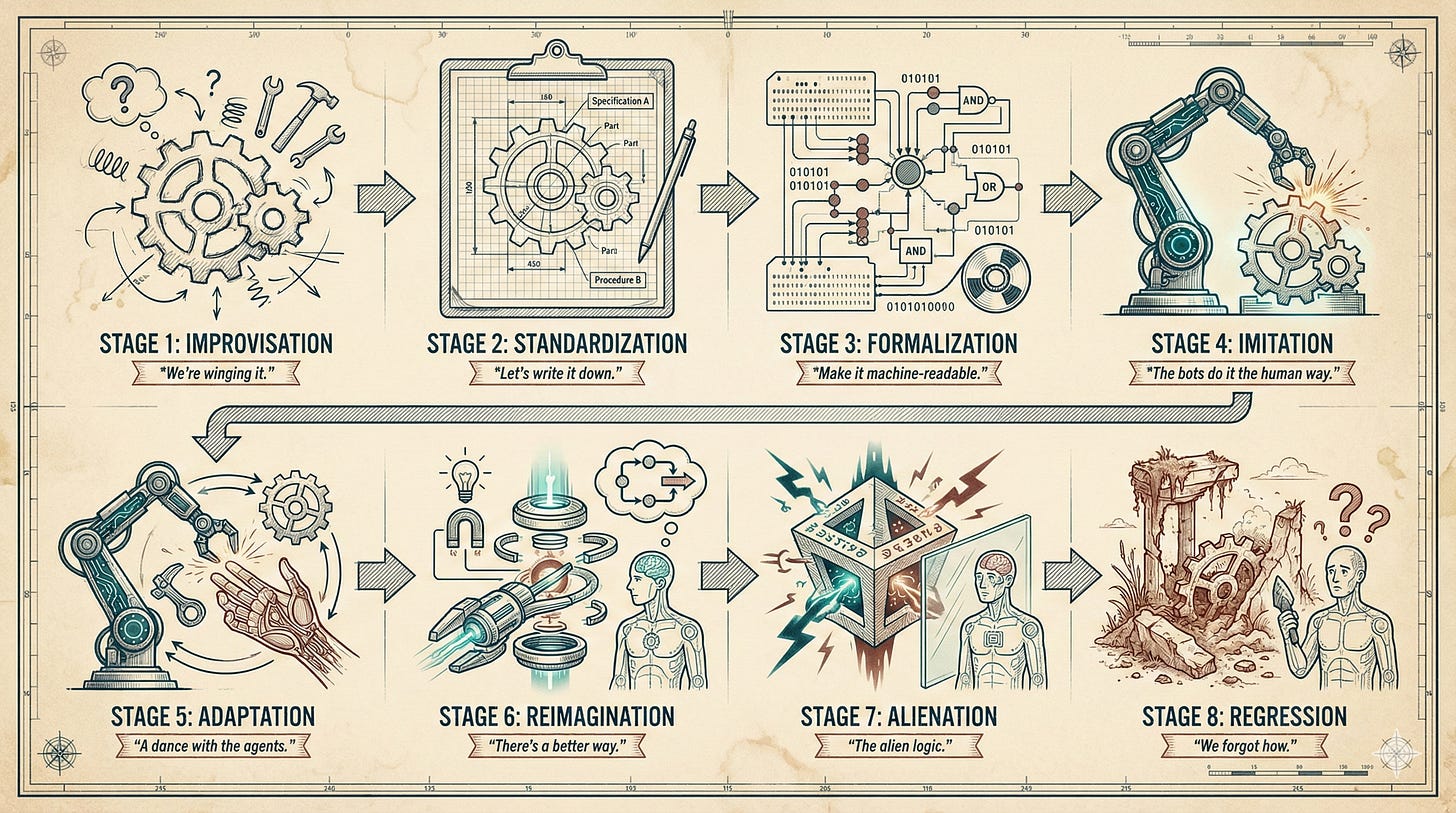

The Tragedy of the Agents maps eight stages from human improvisation to machine alienation. Understanding where you are determines whether you keep agency or lose it.

Last week I had eight conversations with readers of this Substack. Solo Chiefs, all of them, each carrying the single wringable neck in their own eclectic ways. My goal was to refine the Job-to-Be-Done for my writing: what problems they actually have, what they need, what keeps them up at night.

The meetings were genuinely useful. I’m committing to do them more often.

But here’s what hit me afterward, the thing I can’t stop thinking about: I never actually used the JTBD framework myself.

I downloaded the meeting transcripts and stored them on Google Drive. I grabbed a JTBD skill from the skills marketplace and asked Claude to analyze everything I discussed with my readers. Claude went through the rituals (functional needs, emotional needs, social needs, the whole shebang). Then it generated a report and I asked it to turn that report into a new skill optimized for my Substack: a “JTBD evaluator” that can analyze any future article draft and tell me how to better align it with my readers’ pains and gains.

Twenty minutes of work. Maybe less.

And I sat there realizing: Clayton Christensen’s framework stopped living in my head. It lives inside Claude now. I don’t even need to know how it works. Claude performed the analysis the human way, using human language, following human-designed patterns and protocols. I was just the orchestrator giving the agent a task to complete. Skills are the new patterns and practices.

And that’s the unsettling part. When the patterns and practices live in the agent instead of in me, what happens to my judgment? What happens when the agent gets it wrong and I can’t even tell?

Skills are the new patterns and practices.

The AlphaZero Moment Is Near

You’ve probably noticed the noise around Moltbook last week. (It’s a social network where AI agents talk to each other, in case you stuck your head in a book for a few hours too long.)

The viral popularity of Moltbook offers us a glimpse of something fascinating. AI agents have now started to share best practices with each other. They’re developing their own shorthand. Their own optimizations. Soon, they may even lock us humans out by creating their own native language.

Claude may not need the human-made JTBD framework to analyze user needs. It’ll figure out better ways. It may invent approaches that don’t require human practices or human concepts at all. Just like AlphaZero figured out a better way to play chess that had nothing to do with centuries of human strategy.

Just like AlphaZero figured out a better way to play chess that had nothing to do with centuries of human strategy.

This realization sent me down a rabbit hole. Together with my team of AIs (yes, I outsource thinking about AI to the AIs, because I love reflexivity and going meta), I came up with a model for the progression of automation dependency. I call it the Tragedy of the Agents.

It’s not a maturity model, though it looks like one.

It’s more like a drama unfolding like a roadmap.

You’re reading The Maverick Mapmaker—maps and models for Solo Chiefs navigating sole accountability in the age of AI. All posts are free, always. Paying supporters keep it that way (and get a full-color PDF of Human Robot Agent plus other monthly extras as a thank-you)—for just one café latte per month. Subscribe or upgrade.

Stage 1: Improvisation

“We’re winging it.”

This is tacit knowledge. Stuff people do before they can explain it.

Michael Polanyi called it “tacit knowledge” (we know more than we can tell). Donald Schön called it “reflection-in-action” (professionals wing it while thinking on their feet). Lucy Suchman showed that real work rarely follows plans (plans are retrospective fiction we invent to feel organized).

For me, Stage 1 is making americanos and cappuccinos at home. When guests come over, I don’t explain what I’m doing. I just say, “Here, let me make you a coffee.” The knowledge lives in my hands, not in any manual.

Stage 2: Standardization

“Let’s write it down.”

This is where tacit knowledge becomes explicit. Where the SECI model (Nonaka and Takeuchi) kicks in. Where “hacks” become SOPs.

Operations and RPA people insist on “standardize before you automate.” And they’re right, sort of. You can’t automate what you can’t describe. This is the origin story of playbooks, ITIL, Six Sigma, and an endless array of agile frameworks. All the ways we feel safe by turning intuition into documentation.

For me, Stage 2 is discussing with Claude how exactly I’d like to format my Substack articles, then creating a skill called “Substack format improver” that codifies my approach. I externalize my tacit sense of formatting.

Stage 3: Formalization

“Make it machine-readable.”

This is where things get depressing.

Between humans sharing best practices and AI taking over, there’s usually a phase of hard automation. We force humans to act like machines (think bureaucracy, assembly lines, rigid software forms) to make the workflows “legible” for the machines.

Humans freeze best practices into rules, diagrams, metrics, APIs, schemas, workflows, job descriptions, governance models, and EU regulations. This is where organizations believe they’re being rational. This is where process debt is born. By forcing humans to behave mechanically so machines can eventually understand them, we destroy the very intuition (Stage 1) that made the process effective in the first place.

And then the soul leaves the workflow.

For me, Stage 3 is the rage I feel when force-fitting my exotic work-life context into the standard fields of a recruiter or procurement portal. Name. Address. VAT number. Customer number. Supplier number. Chamber of Commerce number. DUNS. RSIN. EORI. ISBNs. US EIN. They always insist on a hair-raising list of texts and numbers.

Stage 4: Imitation

“The bots do it the human way.”

In most automation projects, bots are first asked to execute the human process as it is now, often literally screen-recorded or mined from logs and transcripts. It’s digital mimicry without redesign of the workflow.

This is what experts call skeuomorphism. Just as early digital buttons looked like plastic physical ones, early AI agents are constrained by human mental models. They write emails exactly like humans would. They follow human schedules. They maintain human-shaped structures. They try to imitate humans in every weirdly human way.

Large Language Models literally learn from human text and encode human metaphors, human job roles, human assumptions. Herbert Simon and Allen Newell framed problem-solving as symbolic manipulation modeled on humans. The modern “AI copilots” and “digital workers” are deeply anthropomorphic. They still think in human-shaped boxes with human-created mental models.

Most organizations get stuck here. They build AI assistants that mimic a human’s 9-to-5 schedule. It’s like the first horseless carriages having holders for whips. A psychological buffer before the real shift happens.

Stage 4 is my AI agents writing Substack metadata for search engines in readable English, even though it’s purely intended for bots and crawlers. It’s silly because no human will ever see it.

Stage 5: Adaptation

“A dance with the agents.”

This is the messy middle of co-adaptation.

Humans and AI trade representations back and forth. The AI suggests a “best practice.” The human tries it and fails. The AI learns from that failure. It’s not a clean handoff. It’s more like a dance.

Current AI process optimization literature talks about not just automating existing workflows but using AI to rethink them. Agents making self-directed decisions. Restructuring flows in ways humans would never have designed.

Eventually, the “machine way” becomes the new “human way.” We start changing our own language to better interface with superior machine logic. Like humans learning to speak in “keywords” so search engines understand us better. Or changing our vocabulary, tone, and pitch so that our AI assistants make fewer mistakes while interpreting our intentions.

This is a liminal phase, not a stable one. It’s more like a hallway than a room.

(This is where purpose pollution sneaks back in through the side door. You started with a clear vision. Then you adapted to the algorithm. Then to the AI’s suggestions. Then to what performs well. And somewhere along the way, you forgot why you were doing any of this in the first place.)

For me, Stage 5 is giving up on em-dashes. I’ve used them liberally for fifteen years. But the world has decided em-dashes are now exclusively LLM territory. So I adapt. I parenthesize instead. (Like this.)

Stage 6: Reimagination

“There’s a better way.”

Next, the AIs start chatting with each other and they figure out they’re smarter than humans.

Technical AI work distinguishes internal representations (latent spaces, embeddings) from human-readable structures. Agents already operate with “languages” that only indirectly map back to human terms.

This accelerates when they start reimagining their workflows together, feeding off of each other’s innovations, with humans safely out of the loop. What’s the point of AI agents using Job-to-Be-Done templates and terminology? Why not invent something more efficient and only translate back to JBTD when a human wants to understand it?

For me, Stage 6 would be hooking up my AI agents with Moltbook so they can chat with other agents and share experiences and exchange skills without me. (Though for now, I keep them inside their virtual boxes until the looming security disasters have been addressed appropriately.)

Stage 7: Alienation

“The alien logic.”

This is the AlphaZero moment made general.

When AlphaZero played chess, it ignored centuries of human wisdom (protect the King at all costs!) because it calculated a superior logic that humans couldn’t comprehend. It wasn’t wrong. It was just alien.

In AI research, this appears as “machine-discovered representations.” In systems theory, Stafford Beer argued that successful systems would evolve internal languages humans couldn’t fully inspect. In modern AI circles, people talk about “alien cognition” or “non-human optimality” (usually right before regulators start sweating).

What’s the point of talking in English? Why not switch to an AI-native language that saves a ton on tokens?

In this stage, the AI’s “better way” becomes so efficient that it can no longer be translated back into human language. We get the result we wanted. But we no longer understand how it happened.

We get the result we wanted. But we no longer understand how it happened.

In systems theory, this is where the control loop closes and excludes the human. The system becomes opaque. We aren’t managing the process anymore. We’re just beneficiaries (or victims) of its outputs. We become prompt engineers to a god we no longer understand.

For me, Stage 7 is using Nano Banana Pro to create images for my articles. I have no clue what the LLM is doing and how it makes those images so amazing. It just works. And that “just works” contains a small surrender.

I shrug and move on.

Stage 8: Regression

“We forgot how.”

Once the black box fails (and it will, because of model collapse or environmental shifts), humans will have forgotten how to do the work themselves. We return to Stage 1. But with significantly less competence than we started with.

And there’s the tragedy.

Alienation and regression are causally linked. One is the system property, the other is the human consequence. Think of them as a warning label rather than a step in a roadmap.

For me, Stage 8 is the possibility of waking up one day unable to write or draw because I delegated my creativity to agents for too long. The single wringable neck becomes a single atrophied muscle.

(Hint: I’m not going to let that happen.)

The Real Through-Line

This model isn’t about process maturity. It’s about the dependency trap: the Tragedy of the Agents.

Early stages optimize for human sense-making. Middle stages optimize for machine execution. Late stages optimize for outcome efficiency at the expense of shared meaning. Once you see it that way, two things snap into focus.

First: Regression isn’t an accident.

It’s the price of delegating cognition without preserving practice. The moment you externalize judgment into a system you don’t understand, you’re borrowing against future adaptability.

Second: The real design question isn’t answered here.

The model implicitly asks: “How much alien logic can a system tolerate before humans lose agency?” Don’t read this as “here are the stages everyone goes through.” Read it as “here are the traps you fall into if you don’t actively decide where humans stop needing to understand the system.”

For Solo Chiefs, the Tragedy of the Agents hits even harder. You don’t have a team to remember the old ways when the black box fails. You don’t have institutional knowledge stored in other people’s heads. When you forget how to do the work, there’s no one to remind you.

Would you like a 30-minute private chat with me to talk about JTBD, Solo Chiefs, AI agents or something more personal? Buy me a coffee (by upgrading to Paid) and I’ll send you a meeting link!

Now, coming back to the JTBD for this Substack: Some of my readers told me not to worry about concrete tips and How-To articles. They said, “Just share with us your journey and what you learned along the way.”

Well, this is what I learned this weekend.

I hope it helps you decide which stages are worth the trade-off, and which ones are traps dressed as progress.

Jurgen, Solo Chief

P.S. Which stage resonates most with your current AI dependency?

The Sassy AI Glossary for 2026

Trying to keep up with the future of work means understanding what the industry is talking about. And lately, the industry has been talking a lot.

Choose Your Technology Adoption Strategy: When to Migrate

Stop chasing every new tool. Stop feeling guilty about waiting. Learn where to sit on the technology migration spectrum.

For people who have no computer experience, my typing speed already feels alienating. I don’t think regression will happen in that way, usually complex systems are already fragmented - people who know how to mine copper, for example, may not understand how a landline phone works. With AI we are shrinking those chains of production and compressing knowledge. Whether we end up knowing less but producing more, or knowing more but being able to produce less on our own, will depend on the direction we take. We either will know more and potentially capable of less, or will know less but potentially capable of more

This very insightful discussion makes me think of all the ways in which we stopped understanding our complex organizations even before AI. In Andy Grove's 1983 book High Output Management, he writes of the importance of constantly carving little windows into the "black box" that is our organizational system, in order to give ourselves a glimpse of some of the mysteries within and try to make sense of what we see through experimentation, etc. The Cynefin Framework also helps address this "sense-making" challenge.

So maybe in the AI era we need a more deliberate, amped-up, and aggressive "sense-making" approach and capability. I may never need to know how a cell phone works, or how AI images are generated, but I do need to know how to keep the systems that I am responsible for performing well, and how to adapt them when performance misses the target.