The Truth About Writing with AI (And Why Critics Are Missing the Point)

The reader's experience is more important than the writer's process.

Some readers are calling out authors for using AI in their writing. It's all a bit silly because the only thing that matters is the experience. Yes, even those people who think they care about the writing process are just fooling themselves. It's all just reader experience.

Do you think I wrote this piece with AI?

I'll let you know at the end.

Bring up the topic of AI-assisted writing on Substack or in any writers' Facebook group and watch the pitchforks emerge. Many creators see the use of generative AI and virtual assistants in creative works—whether it's books, graphics, films, or music—as uninspired at best, blasphemous at worst. "Plagiarism!" "Heresy!" Yet, those same creators have a rich history of collaborating with and even relying on tools and other humans when crafting their works of art.

All Creators Use Other People's Work

It's common knowledge, for instance, that Leonardo da Vinci collaborated with numerous apprentices across a vast array of artistic endeavors, including murals, paintings, and frescos. He claimed credit for any artwork that emerged from his workshop—"Virgin of the Rocks," "Salvator Mundi," and even "The Last Supper"—regardless of who actually wielded the brush. Leonardo's workshop was a finely tuned machine. He would sketch out compositions and let his team handle sections, saving his own genius only for the crucial elements like faces, hands, and his personal signature touches. And nobody batted an eye.

Likewise, I can't count the number of books I've read by popular scientists, business leaders, or celebrities that left me inspired and energized. Not once did I wonder if these authors wrote every word themselves. Many used ghostwriters, since the art of writing doesn't come naturally with being a successful inventor, politician, or manager. From A Brief History of Time (Stephen Hawking) to Becoming (Michelle Obama) or Like a Virgin (Richard Branson), none of these masterpieces were penned by the people whose names graced the covers. And nobody holds it against them.

Even in music, some of the most celebrated artists in history didn't write their own songs. Elvis Presley, the King of Rock and Roll, built his career on the lyrics and melodies of others, delivering them with his signature charisma and style. Yet, nobody is up in arms about his lack of authorship. Apparently, it's perfectly acceptable to borrow a creative brain or two—or even two thousand. As musicians themselves acknowledge:

"If you steal from one artist, it's plagiarism; if you steal from many, it's research."

- Tony Bennett, American singer

And when new technologies accelerate that "research," few music lovers will complain.

In the film industry, directors and actors get the glory, but behind every blockbuster is an army of screenwriters, editors, cinematographers, and visual effects artists. George Lucas didn't single-handedly craft the Star Wars universe—he relied on countless talented individuals refining scripts, designing costumes, and creating otherworldly landscapes. Stunt doubles, sound engineers, and CGI teams all played their part. Few Star Wars fans care that the director assembled significant portions of these movies through collaboration with human helpers or digital tools—while liberally shoplifting from the Dune, Flash Gordon, and Lord of the Rings storylines. What mattered was the experience.

Digital art tells a similar story. Photoshop has been the backbone of design for decades. Artists manipulate, enhance, and transform their works with software, and nobody sneers at their use of Wacom tablets or Lightroom presets.

Yet, swap out those tools for artificial intelligence, and suddenly, all hell breaks loose.

Only the Experience Matters, Not the Process

The truth is that creativity has always been a blend of individual inspiration and external innovation, whether the collaborators are human, mechanical, or algorithmic. AI is just the latest in a long lineage of tools that amplify our capacity to create. Maybe it's time we embraced the inevitability of its role in the creative process—if only to avoid the hypocrisy of pretending we've always done everything ourselves.

I once debated with a mob of fiction fundamentalists who insisted that the goal of every part of a novel is to "advance the story." Each word, sentence, paragraph, and chapter should "move the narrative to its conclusion." I told them it was all nonsense. They were dead wrong, probably because I approach things from a business perspective. A novel is a product, just like any other. The goal of each product is to deliver the user a compelling experience. As long as readers keep turning pages, the author has succeeded. Let's be honest: The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy is widely celebrated for its digressions, absurdist humor, and philosophical musings that don't advance the story in any meaningful way. Yet the experience of reading it has transformed it into one of the most beloved books of all time. Same with Lord of the Rings: the entire Tom Bombadil section is utterly pointless. Does it advance the story? Not in the slightest. Does anyone care? Absolutely not.

The only thing that matters is the reading experience.

Do people keep reading? If yes, all good.

Nothing else matters.

The Perceived Process Is Not the Actual Process

"But, but, but…" I hear some people protest, "I care about the author's writing process. I care about the fact that every sentence of the text I read was handcrafted by an actual human, not by an algorithm or a machine."

Well, I'm sorry to burst their bubble, but these people are deluding themselves. They care only about believing that the production process somehow avoided AI contamination.

Evidence from research shows that most people cannot distinguish human-made text from AI-generated text. They can't even tell apart human-made art from AI-generated art. But yes, most of those same humans do have a preference, the research confirms. They have a preference for what they believe to be handcrafted. If people think that something is machine-generated, they lower their appreciation of it, regardless of whether the work was actually made by a machine or by a human. And vice versa, if they think that something is handcrafted, they rate it higher, regardless of whether the art piece was actually the product of a human or a machine.

People care about the perceived creative process, not the actual creative process, because they can't even tell the difference! But the crucial point: the perceived process is part of the outcome and experience. It's not the actual process itself.

For example, my readers cannot appreciate my actual writing process unless they're there during the creation of the text. And to be honest, I don't think I can write decent essays with people looking over my shoulder. It feels rather unsettling and intrusive. I'd like to write all by myself, with a cup of coffee, thank you very much. My readers can only appreciate how I make them feel about my writing process. In other words, how I present it to them and how I discuss it. And that, my dear reader, is product experience, not process.

Consumers cannot care about the process of how a product was created. They can only care about what they believe to be the process. And this distinction is crucial. Product marketers ruthlessly exploit this gap. That's why they slap all kinds of FSC, GOTS, USDA, Fairtrade and Leaping Bunny logos and stickers on products that make you feel you're buying something that is artisanal, sustainable, ethically sourced, and so on. But it could all be a steaming pile of marketing BS. Product managers and marketers care about manufacturing a feel-good experience.

So, the conclusion remains the same: the only thing that matters is the product experience. And for some people, that includes how you make them feel about your production process.

The Tools Are Also Made by Humans

"But, but, but…" I hear some people respond. "The stunt people in the movies are still human. Human animators make the CGI animations. Leonardo da Vinci's apprentices were human. The ghostwriters who write for celebrities are still human. And humans also made the melodies borrowed by Tony Bennett. None of them were machines."

Of course, they were. And hopefully, the humans to whom part of the production process was delegated got properly compensated for the roles they played. Likewise, the makers of Adobe Photoshop get paid. The programmers at ProWritingAid get paid. And the makers of my Faber-Castell and Winsor & Newton pencils get paid. Just like all those humans working for OpenAI, Claude, Gemini, xAI, Meta, DeepSeek, and the other AI labs would like to get paid for the work they do making these powerful LLMs available to creatives. They all get compensated, and all of them are human.

It doesn't matter that part of a production process comprises tools, machines, and software. These intermediary products are still made by people. So, what's the point of insisting that the work is done only by humans? Behind every creative tool, there's still a team of humans.

There Are Many Ways to Use AI

"But, but, but…" I hear other people say. "AI is trained on the work of unpaid artists! It is unethical to use a tool that was created from stolen materials."

Indeed, LLM development is in a Wild West phase right now, like downloadable music was in the 90s. (Anyone remember Napster?) I sincerely hope the copyright matter will soon be resolved in the courts. And if not, the lawmakers will step in. This needs to happen sooner rather than later. But that's an entirely separate discussion worth having at another time. Meanwhile, the technology isn't going away, so we'd better get used to the idea that there are AI tools that can help people with their writing. (And we should do all we can to ensure that those AI tools were ethically trained.)

Note: Claude flagged my dismissal of the copyright issue as violating my Accountability value, but I see this differently. If the world stopped using AI altogether, there'd be no need to address the copyright problem. We can only keep pressure on lawmakers by simultaneously continuing to use LLMs *and* supporting copyright holders in their fight so that they also get paid fairly for their work.

What bothers me most is that the critics seem to forget there are many ways to have AI assist authors in their writing. AI can generate ideas. It can write a first draft. It can review first drafts. It can comment on structure and synopsis, rewrite early versions, comment on the rewrites, assist with style, grammar, and spelling, condense, expand, or translate specific sections, or repurpose a text for another medium. In other words, what do the critics actually mean when they call out an author for "using AI in their writing?" Did the author do just one of these things? Several of them? Or all of them? It makes quite a difference whether an author generated an entire Substack post with just one tap of a button or spent fifteen hours fine-tuning an essay (such as this one) with an AI collaborator that was merely giving feedback.

Welcome to The Maverick Mapmaker — where M-shaped, multidisciplinary professionals learn how to orchestrate work between humans and AI. If you refuse to be put in one box… if your mix of skills is your edge… if you want tactics for thriving in the age of AI without falling for hype or doom — this is your place. Stay sharp, stay multidisciplinary, and stay ahead. Subscribe to my Substack now.

Authors Are Facing a Dilemma

It's worth noting that the question of what to communicate to readers about a writing process (what to make them believe about it) can be quite a dilemma for authors. As we've seen, many readers have a bias against the perception of AI-written materials. This means that when you authentically share that you've used AI in some parts of the process, a portion of the audience will automatically downgrade the quality of your work, regardless of how good or bad it actually is. Likewise, when you're very skilled at prompting the machines to generate a text that's indistinguishable from handcrafted prose, your readers may give you the Artisanal Perception Bonus: they assume no AI was involved and will thus rate your work more highly!

Of course, when you lie to your consumers about your production process (as the aforementioned product marketers sometimes do) and people later discover that you've been deceiving them, you have a new problem on your hands: greenwashing, public deception, and inauthenticity will then be part of your brand and the product experience you've delivered. Good luck recovering from that. (Anyone remember H&M's "Conscious Collection" or Apple's "carbon neutral" smartwatches?)

The lesson for AI-assisted authors seems to be: either be authentic about what you do, ensuring that people's perception of the process aligns with your actual writing process, or hide the truth of your AI usage so well that nobody will ever find out. My best guess is that the former is easier than the latter.

Note: Claude flagged the idea of user deception in the last paragraph as potentially conflicting with my Transparency value, not fully appreciating the intended sarcasm. I'm sure my readers are smart enough to understand I don't support deception.

Yes, I Also Use AI (to Some Extent)

In case some of you were wondering, I write my entire drafts by hand, and I rework them until I'm satisfied with what I want to communicate to my readers. Only then do I ask Claude to give me feedback on structure and whether the post I wrote aligns with my core values. (It is roughly equivalent to using AI as a structural editor.)

After processing Claude's feedback, I fine-tune the text for how I want to deliver my message. I may add a joke, a jab, a pun, or whatever makes the text more engaging to read. And then I ask Claude to rewrite the entire thing at the sentence-level: it is only allowed to change some words and phrases for better flow and readability. (This is roughly equivalent to using AI as a copy editor.)

I try to remove any AI "tells" in my writing (such as "foster", "delve", or too many em-dashes), regardless of how they ended up in the text. As I keep saying, the process is irrelevant, so it doesn't matter whether it was me or Claude who added the bullet points or the corporate lingo. If it might give readers the wrong impression of my writing process, it needs to go.

My writing ritual ends with a back-and-forth between me and the AI about an effective title, subtitle, leading paragraph, and SEO summary, before I hit the publish button.

So, am I using AI in my writing? Yes.

Should it matter to anyone? No.

The only thing that matters is, did you appreciate the experience I just delivered? If the answer is “Yes,” I suggest you subscribe or upgrade. I have plenty more coming.

Jurgen

P.S. Part of this text is adapted from the opening in my book Human Robot Agent.

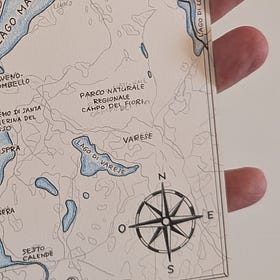

I Started Drawing Maps

My new experimental hobby reflects something crucial about survival in the future of work: the rise of M-shaped professionals.

Using the System Against Itself

Let's ensure that the toys of tech billionaires help create the very organizations they would never build themselves.

Oh, I see your Claude also developed a preachy personality that skims the text instead of doing a full read. Thank you for the article! It's difficult for some to understand AI cannot produce the thoughts and ideas behind one's work, but it will build on them. And why not give the reader the best way to phrase a great idea?

Interesting piece Jurgen